Dearest Son

- Kristan Higgins

- Jul 22, 2017

- 4 min read

Updated: May 3, 2022

Dearest Son was due on Valentine’s Day; he came on December 6, an emergency c-section in the middle of the night requiring a two-and-a-half-month stay in the hospital.

They didn’t show us his face when he was born— “It’s a boy, Kristan, you have a son,” Dr. Dolan said and handed him off to the neonatologist. No cry. Limp baby, not breathing. Please, I prayed to God, Jesus, my father, that one word that every mother has branded on her heart. Please.

We heard a cry, a loud, sustained scream, and I burst into tears of joy. My boy. My tiny boy, one pound, ten ounces, full of sound and fury, signifying everything.

For the next 76 days, I sat next to his incubator, which we decorated with pictures of his big sister, and two beanie babies—a lamb and a pig. When his sister, not quite three, came to see him for the first time, she sang him the ABCs, and he turned his head toward her and opened his eyes.

We were told about the chance of brain bleeds and GI problems, developmental delays, and physical disabilities. “Don’t you worry,” I told my tiny son. “Whatever happens, we’ll take care of you. All you have to do is live.”

His name in Irish means gleam, and man of prayer, possibly the most fitting name for a baby ever, given the number of prayers said for him. His remarkable brown eyes gleam daily. As a toddler, he was full of energy, scrappy, and mischievous. The day he learned to walk was also the day he learned to run. He loved to eat the cat’s food and hide in the cupboard, stealing chocolate chips. His sister would bring him in for show-and-tell, and all her friends were his as well.

At his nursery school parent-teacher conference, the teacher started to cry. “I can’t tell you how much I love your son,” she said. It was a reaction we’d get again and again. In kindergarten, he donated all his allowance money to the victims of Hurricane Katrina. He was the student who’d stay to help the teacher clean her room, or carry boxes. He has an innate kindness, a knowledge for knowing when someone needs a little more. He was always small, but he’d defend kids against bullies twice his size, furious at the injustice.

We insisted that both kids stay in karate until they had their black belts. To our shock, this boy who had to be forced to practice, whose sister had to teach him the forms over and over, completely aced the grueling all-day test. He was eleven.

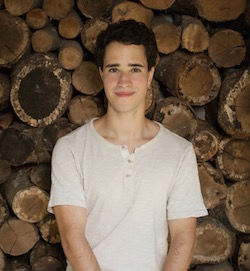

As he grew older, he learned that a sense of humor could defuse tension better than outrage. He’s kind to the elderly—his high school community service consisted of writing memoirs with people at the local nursing home. Women love him—his curly dark hair, his eyelashes. He’s used to it.

Both kids were required by their parents to do a team sport since it was good for the soul. Dearest reluctantly chose cross-country. He hated it. He would walk half the course. Shin splints, he’d say, or a tough course. “Just do your best,” we said.

In high school, he surprised us by staying on the team. At each meet, he’d gamely finish last, always smiling as the parents of the faster kids—and his own parents—cheered him on. There was that one time when I managed to say the right thing at the right time, driving him home after a meet. “It takes a lot of character to enter a race, knowing you’ll come in last,” I said. “I can’t tell you how much I admire that.”

When he was a junior he started training extra, talking to the coaches. He no longer finished last. His work ethic and attitude were exemplary, and his teammates voted him captain his senior year. That was the year the regional qualifications changed, dropping the qualifying time, which meant our son would have to take his very best time and improve it by twenty seconds…in one mile. “Do you think you can do it?” I asked him. “Coach and I both know it’s a long shot,” he said.

During a meet on a cold spring day, his father and I leaned on the fence, watching the mile run. By the second lap, it was clear our son wouldn’t make it the time he needed; he was barely on pace, and runners tend to get slower in the second half. But he ran a hard third lap, Coach calling out his time. And in the fourth lap, something happened. Our son’s stride lengthened. He started closing in on the runner 30 yards ahead of him. Dearest Son was breaking away, and his team and all the parents cheered madly for him that last half lap.

He came tearing down the home stretch and met the qualifying time with four seconds to spare. His whole team went crazy, and our boy…well, he looked across at his dad and me and gave a little nod. “Get over here!” I said, sobbing happily, and he did, giving us sweaty hugs.

He loves his grandmothers and extended family, my sister especially. He plays with our dogs, teaches them odd tricks, woos the cat, bickers with and laughs with his sister, who is still his best friend. He can make me laugh till my teeth chatter, and does a dead-on impression of me. In many ways, he is father’s boy—hardworking, quiet, focused on the things he loves. I know he is mine as well—the sense of humor, the love of a lazy day. Mostly, though, he is himself.

In less than a month, my son will go to college. I hope he’ll bring Lambie and Piggy, as the Princess brought Ernie, but he’s a rather dignified person, so we’ll see. He’ll run cross-country and study government. He wants to go into politics, and I’m glad, because the country could use someone with his integrity, intelligence and heart. He has a plan and a strategy for doing well, and I have no doubt that he will make the world a better place. He already has.

It will be odd, having a day that doesn’t revolve around my children’s schedule. Strange not to have my boy at the dinner table, or asleep upstairs in his messy room. I’ll miss him terribly, my little boy, and yet it’s time. He’s ready. He did what I asked of him eighteen years ago—he made it. He’s so much more than the boy who lived…he is the boy, the young man, who shines.